Sacred places in the Andes: 7 secrets of Machu Picchu

Perched high among the foothills of the Andes, the ruins of Machu Picchu continue to reveal the secrets of the Inca Empire. While the archaeological site attracts large numbers of visitors to Peru annually, here are 10 lesser-known secrets hidden beneath the layers of history.

Show key points

- Machu Picchu is often mistaken for the legendary lost city of the Incas, but it is not Vilcabamba, the true hidden capital.

- When Hiram Bingham rediscovered the site in 1911, local families were already living there, suggesting it was never fully lost to history.

- Built over two fault lines, its mortar-less stone construction allows buildings to survive earthquakes by shifting and settling back into place.

- ADVERTISEMENT

- A significant portion of Machu Picchu's engineering marvels lies underground, including drainage systems and deep foundations.

- Although visiting the site can be expensive, budget travelers can hike the original trail for free with rewarding scenic views.

- The Manuel Chávez Ballón Museum, located off a hidden path, offers insightful context about Machu Picchu's construction and significance.

- Besides the popular Huayna Picchu climb, the lesser-visited Mount Machu Picchu provides even more breathtaking panoramic views.

It's not actually the lost city of the Incas.

When explorer Hiram Bingham III encountered Machu Picchu in 1911, he was looking for a different city, known as Vilkapamba. This was a hidden capital to which the Incas fled after the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in 1532. Over time, it became known as the legendary Lost Inca City. Bingham spent most of his life claiming Machu Picchu and Vilkapa to be the same city, a theory that was only proven wrong after his death in 1956. (The real Vilcabamba is now believed to have been built in the forest about 50 miles west of Machu Picchu). Recent research has raised doubts about whether Machu Picchu has ever been forgotten. When Bingham arrived, three families of farmers were living at the site.

Recommend

It is not strange to earthquakes.

Stones in the most beautiful buildings in the Inca Empire did not use any mortar. These stones were cut so precisely and crammed together so closely that no credit card could be inserted between them. Apart from the obvious aesthetic benefits of this style of construction, there are engineering advantages. Peru is a seismically unstable country - both Lima and Cusco have been hit by earthquakes - and Machu Picchu itself is built over two fault lines. When an earthquake occurs, the stones in the Inca building are said to "dance", meaning they bounce through tremors and then fall back into place. Without this method of construction, many of the best buildings known in Machu Picchu would have collapsed long ago.

A lot of the most impressive things are invisible.

While the Incas were famous for their beautiful walls, their civil engineering projects were incredibly advanced as well. (Especially, as is often noted, for a culture that did not use draughts, iron tools or wheels.) The site we see today had to be carved from a crevice between two small peaks by moving stones and earth to create a relatively flat space. Engineer Kenneth Wright estimated that 60 percent of the construction done in Machu Picchu was underground. Much of this consists of deep building foundations and crushed rock used for drainage. (As anyone who has visited Machu Picchu in the rainy season can tell you, Machu Picchu receives a lot of rain.)

You can walk until you reach the ruins

A trip to Machu Picchu is a lot of things, but cheapness is not one of them. Train tickets from Cuzco can exceed a hundred dollars per ticket, and the entrance fee ranges from $47 to $62 depending on the options you choose. Meanwhile, a round-trip bus journey up and down the 2,000-foot cliff above which the Inca ruins lie costs another $24. However, if you don't mind exercising, you can walk up and down for free. The steep trail follows the 1911 Hiram Bingham Trail and offers extraordinary views of the Machu Picchu Historic Reserve, which looks almost the same as it was in Bingham's time. The climb is tedious and takes about 90 minutes.

There is a wonderful hidden museum that no one goes to.

For visitors who are used to the illustrations in national parks, one of the strangest things about Machu Picchu is that the site provides almost no information about the ruins. (This deficiency has one advantage – the effects remain tidy.) The Manuel Chávez Ballón Premium Site Museum (entrance price $7) fills many blanks on how and why Machu Picchu was built (exhibits in English and Spanish), and why the Incas chose such an exceptional natural site for the castle. But first you need to find the museum. It is uncomfortably hidden at the end of a long dirt road near the base of Machu Picchu, about a 30-minute walk from the town of Aguas Calientes.

There is more than one peak to climb.

Long before dawn, visitors line up eagerly outside the bus station at Aguas Calientes, hoping to be among the first people to enter the site. Why? Because only 400 people are allowed to climb Huayna Picchu daily (the small green peak, shaped like a rhinoceros horn, which appears in the background of many photos of Machu Picchu). Almost no one bothers to climb to the summit that anchors the opposite end of the site, commonly called Mount Machu Picchu. At 1,640 feet, twice as high, the views it provides for the area around the ruins – especially the white river Urubamba winding around Machu Picchu like a coiled snake – are stunning.

There is a secret temple.

If you're one of the lucky early birds that gets a place on the guest list to Huayna Picchu, don't just climb the mountain, take some pictures, and then leave. Take your time to follow the terrifying path that leads you to the Temple of the Moon, located on the far side of Huayna Picchu. Here, a ceremonial mausoleum was built in a cave lined with magnificent stonework and niches that were previously likely used to preserve mummies.

![]()

The Ultimate Swallowers: Exploring the Voracious Nature of Black Holes

Black holes are mysterious giants with immense gravity that swallow everything—even light—making them terrifying and fascinating. With their super-powerful pull and potential to distort space-time, they capture scientists’ and dreamers’ imaginations. Are they evil forces or just strange cosmic rules at play? The mystery continues to deepen. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

The impact of virtual reality on communities and people around the world

Virtual reality is changing how we live, from exercising at home to experiencing full games and even seeing houses before buying them. But too much use, especially by kids, can lead to disconnection from reality and health issues. It’s up to the user to choose how VR affects their life. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

The future of food and technology - expectations you will not believe!

Technology & The Food Future - Unbelievable Expectations more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Why are there 24 hours a day and 60 minutes an hour?

Ever wondered why clocks have 12 hours? It traces back to ancient Egyptians and Babylonians who used finger joints to count and stars to track time. Their clever systems shaped the 24-hour day and 60-minute hour we still use today. Time, it turns out, is a gift from history! more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Embracing stupidity: the hidden value of our mistakes

Embracing stupidity: the hidden value of our mistakes more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

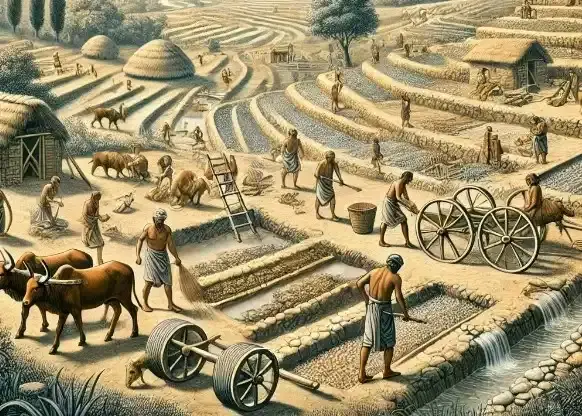

Neolithic revolution

The Neolithic Revolution more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Islamic Hijri calendar – its history, uses and possible improvement

The Hijri calendar, rooted in the 622 CE migration of Prophet Muhammad, holds deep spiritual and cultural meaning for Muslims. It guides key religious practices like Ramadan and Eid. While traditional sightings vary, astronomical calculations offer hope for more accurate and unified observances across the global Muslim community. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

The city of Rimini on the Adriatic coast with its Roman history

Rimini blends beachside charm with rich history—from ancient Roman arches to Renaissance castles. Wander through art-filled streets, savor local pasta and fish soups, and explore unique spots like the Jampalonga Library or Fellini's first home. By the sea or in town, Rimini never stops giving. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

The most expensive mistakes in history

The most expensive mistakes in history more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Many amazing things your nails can tell you

The Many Surprising Things Your Fingernails Can Tell You more- ADVERTISEMENT