Which determines whether it smells good or bad?

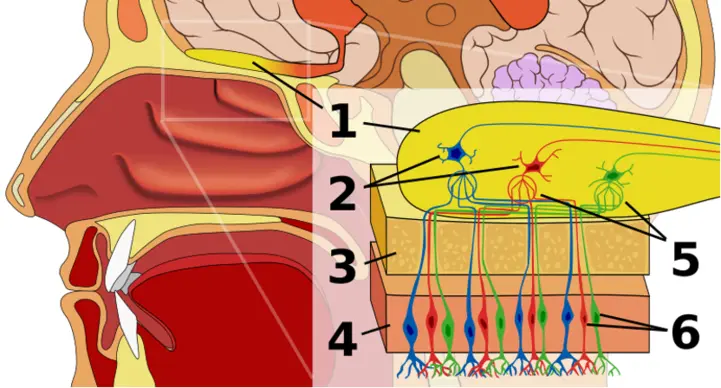

The air is filled with many small odor molecules secreted by objects such as perfume or food. Your nose has the amazing ability to smell thousands of different scents because it contains millions of odor receptors – cells that can recognize odor molecules. When you smell air, these special cells are alerted, sending a signal to your brain that recognizes them. For example, the smell of baked biscuits is made up of many odor molecules. Your brain can accumulate all this information and tell you that there are biscuits that are baked in the oven. In this article, we show the relationship of good and bad smells to memories and human evolution.

Show key points

- The human nose contains millions of odor receptors that can detect thousands of different scent molecules emitted by everyday objects like food and perfume.

- Our perception of pleasant or unpleasant smells is shaped by a combination of genetic differences in odor receptors and personal life experiences.

- The brain links smells with memories—both good and bad—making certain scents triggers for emotional or nostalgic reactions.

- ADVERTISEMENT

- Pleasant odors activate the brain's reward system, particularly through the release of dopamine, which reinforces enjoyable experiences and behaviors.

- Some smell aversions, such as to rotten eggs or blood, are instinctive and serve as biological warnings to keep us safe from harm or illness.

- From birth, humans show innate responses to certain smells, reflecting evolutionary adaptations for survival and food safety.

- While some olfactory preferences are inborn, new experiences can modify how we respond to various odors over time due to the brain’s adaptability.

Smell perception:

The pleasure of perceiving odors depends on our genes and experiences. Hence the olfactory sensitivities associated with the quality and quantity of odors vary on a genetic and cerebral basis. In fact, not everyone has the same number of odor receptor families, nor the same exact amount of these receptors, which can dramatically change our perception and preferences. For example, some people have been shown to smell more cilantro than others. This overstimulation results from the fact that these people have a large number of receptors specific to this smell. To this genetic variation are added life experiences.

Recommend

On a birthday or holiday, our memories are characterized by specific olfactory signatures: the smell of chocolate cake, or the smells of the beach and sea on the coast, which are always perceived in a pleasant way. The same places and the same smells, but this time someone else is unfortunately in an accident. The smells of the coast then become negative, as they were associated with a dangerous or risky situation. The brain is therefore constantly building connections between our sensory perceptions and our experiences, a mechanism that largely guides our behavior. So, it is our genetic past and the context of perception of new smells that gives us our own abilities to detect and appreciate odors. Smells are classified according to their equivalence and our perception of them, either in a pleasant, neutral or unpleasant way... Everything can change under the influence of new experiences, as the brain is a constantly adaptive organ.

Olfactory brain complexity:

Olfactory pleasure is strongly associated with the activation of the brain's reward circuit, which includes neurotransmitters, the molecules that allow communication between neurons. This is especially the case for dopamine, which plays a crucial role in the sense of pleasure and reward. When an odor is perceived as pleasant, the reward circuit is activated, releasing dopamine into the body. This dopamine strengthens the link between fun experiences (birthday + chocolate cake + family + friends + gifts), and stimulates similar fun-seeking behaviors; we look forward to our next birthday to relive this pleasant situation with positive smells. Pleasure and resentment also depend on feelings such as joy or disgust, which are expressed through the activation of the amygdala body in the brain.

Scents that make memories:

The brain is very good at keeping good and bad experiences and associating certain smells with them. Scientists call these memories "olfactory memories." An example is when you smell your favorite meal. It may remind you of someone who made them for you, stimulating your brain to release chemicals that make you feel good.

Of course, the smell can also be associated with unpleasant experiences. Maybe you've eaten some spoiled foods, and now you find yourself hating them, even if they're not spoiled. Here, your brain associates the previous illness with that smell, preventing you from eating something that might be bad for you.

Warning odors:

But what about things that you know smell good or bad even if you've never tried them before? Scientists have found that although many of the scents people love come from past experiences, instincts play a big role. Smell tells you a lot about your environment, and your instincts help you determine what's safe or dangerous. For example, blood has been shown to repel humans and many animals, such as deer, but attracts predators, such as wolves. This steers people away from predators that might want to eat us, but it allows the predator to have their meal. The smell can warn you when something may make you sick. When eggs rot, bacteria multiply crazily inside them, breaking down proteins that release a toxic chemical called hydrogen sulfide. This produces a foul odor that makes you want to stay away, preventing you from eating eggs and getting sick.

Good smells and bad smells:

Olfactory preferences appear very early in our lives, from the moment we are born. Innately, smells containing sulfur, for example, in nature indicate the presence of rot or poisonous plants. It is therefore repulsive to newborns, who have never smelled it before. The reason here is evolutionary, as organisms that cannot detect and perceive this type of smell have not been able to survive. We are now all equipped with a brain circuit that associates the smell of rotten eggs with distinctive facial expressions that indicate disgust. However, sulfur odors will only partially remain repellent to adults; we are very sensitive to the sulfur smell of city gases, but the sulfur smells from cooking garlic do not alienate people who enjoy eating it. Conversely, some very rare scents, such as vanilla or banana, can be felt instantly and pleasantly by a newborn. But a person's response to it may develop with age, becoming poor.

![]()

The Science Behind the Fireworks: Detecting Magic in the Sky

Fireworks light up the sky with magic, but behind the scenes, it’s all science—from chemistry creating dazzling colors to physics shaping every explosion. With modern tech, they’re safer and even eco-friendlier, blending beauty and brains for unforgettable shows that wow us while caring for the planet. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

The Dream of Getting Rich Quick: Stories of Turning Good Fortunes into Millionaires Overnight

Overnight Millionaires: People Who Got Rich Quick more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Sama Beirut... Unique skyscraper

Sama Beirut, Lebanon’s tallest tower, rises with elegance in Achrafieh, offering stunning sea and mountain views. Built by Fadi Antonios out of love for his homeland, it blends green space, luxury living, and modern safety features—all in one iconic landmark symbolizing hope and resilience. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Is the universe still making new galaxies?

Is the universe still making new galaxies? more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Topkapi Palace ... The largest palaces of Istanbul in Turkey

Topkapi Palace, once home to Ottoman sultans, dazzles with over 12,000 porcelain pieces and secretive chambers. Known as the "Palace of Happiness," it’s now a UNESCO World Heritage Site and ranks among Europe's most visited museums, drawing millions into its rich blend of history, culture, and architectural beauty. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Moving forward still represents progress: trusting the process and taking my own best advice

Moving forward still represents progress: trusting the process and taking my own best advice more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

At each moment, there are about 2,000 thunderstorms occurring on Earth.

Thunderstorms are powerful and common, with up to 2,000 happening worldwide at once. Florida tops the U.S. in stormy days, but Venezuela's Lake Maracaibo holds the lightning strike crown. When thunder roars, go inside—lightning is closer than you think and more dangerous than most realize. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Alert from the Northern Lights: Sun's activity is at its highest level in 23 years with the Northern Lights

Alert from the Northern Lights: Sun's activity is at its highest level in 23 years with the Northern Lights more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Shocking fact: the moon is moving away from the earth!

The Moon is slowly drifting from Earth—about 3.8 cm a year—thanks to tidal friction. This tiny shift, tracked since NASA's Apollo missions, may eventually lengthen our days. Don't worry though; the Moon won't escape. It'll settle into a stable distance over time. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Eastern musical maqams and western stairs

Eastern musical maqams and western stairs more- ADVERTISEMENT