What is the birthday paradox? And is it real?

If I invite a group of people to a party, how likely are some of them to share the same date of birth? The birthday paradox is a mathematical phenomenon that shows the probability of having two people in a group with the same date of birth. The result may amaze you. In this article we show this paradox and explore this wonderful mathematical concept.

Show key points

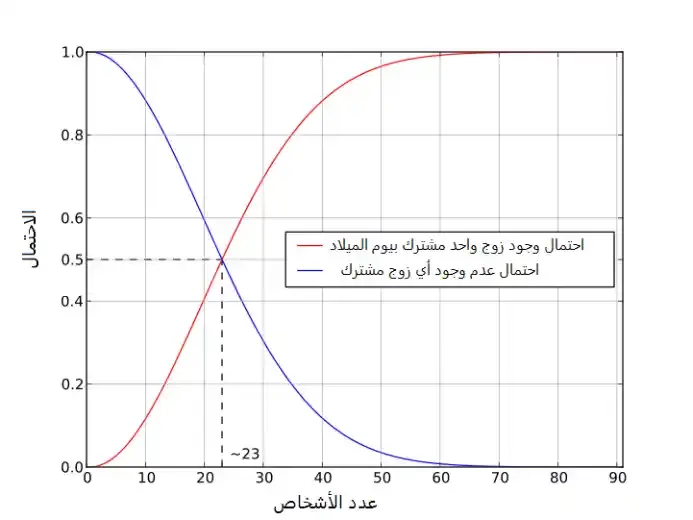

- The birthday paradox reveals that in a group of just 23 people, there's over a 50% chance that at least two individuals share the same birthday.

- This surprising result contradicts our intuition, as many people assume much larger groups are necessary for such coincidences.

- The key to understanding the paradox lies in realizing that you're not comparing one person to the entire group, but checking all possible pairs for shared birthdays.

- ADVERTISEMENT

- Mathematically, the probability that no two people share a birthday is easier to compute, and it decreases rapidly as the group size increases.

- With each additional person in the group, the number of unique pairs increases significantly, raising the odds of a shared birthday.

- When the group reaches 70 individuals, the probability of at least two people sharing a birthday exceeds 9

- 9%, making it virtually certain.

- The paradox highlights how human intuition often fails when dealing with probabilistic scenarios involving multiple comparisons.

What is the birthday paradox? And why is it surprising?

The birthday paradox is an amazing concept in probability that shows how likely two people are to participate in a group on the same date of birth. In a group of just 23 people, there's a greater chance of at least two people sharing the same birthday. Of course, this possibility increases rapidly as each additional person is added to the group. The "paradox" comes from the fact that the result is very counterintuitive, because most people would guess that the probability should be much lower, i.e. we would need a much larger number of 23 people to achieve it. In fact, it may seem at first glance that we will need at least half the number of days of the year (about 182 people) to have a 50% chance of a joint birthday, because there is a 1/365 chance that someone else will have the same date of birth as you. What confirms our intuition is that you've met many more than 23 people, but you don't know anyone who shares your birthday (or you know but very few). How can this be true?

Recommend

Solve the puzzle:

Surprisingly, the number 23 is perfectly correct, and it can be proven mathematically. The key is that our simple intuition ignores the fact that we have to not only check the date of birth of one person compared to others, but also check all possible pairs of people in the group. In other words, we're not just comparing someone's birthday to everyone else's birthday, but we're comparing everyone in the group to all the other people in it. With 23 people, there are many different couples of people whose dates of birth we can compare.

For example, imagine that the group consists of only two people: you and another person, only one pair. There is actually a small possibility (1/365) that you both have the same day of birth. Now that a third person is added to the group, there are three pairs to compare: you and the second person who was with you, you and the third person who was added, and the second person with the third. As more people are added, the number of couples will increase a lot, so the chances of two people sharing the same birthday also increase. By the time you have 23 people in the group, there are 253 couples to compare, and it is this large number of comparisons that makes the probability reach about 50%.

Full mathematical answer:

To better understand the problem, let's first determine the situation mathematically. Let's say there are 365 days a year, and we ignore leap years for the sake of simplicity. We want to calculate the probability that in a group of n people, at least two share the same date of birth. Each person's birthday is supposed to be equal on any of the 365 days, and birthdays are independent of each other. It's easier to calculate the supplementary probability (i.e., the probability that no one will participate on the date of birth), and then subtract this from 1 to get the probability that at least two people will participate on the date of birth.

First - the case of one person: The first person can have any birthday, so the probability that their date of birth is unique is 1 (i.e. 100%).

Case of two persons: In order for the date of birth of the second person to be different from the date of birth of the first person, he has 364 options (out of 365), since the first person has already taken a day. The probability is 364/365.

Third: For a third person to have a different date of birth than the first two, they have 363 days to choose from. The probability is 363/365.

Pattern persistence: When we add more people, each new person has one less day available to choose from to avoid sharing their birthday with the rest of the group. For the fourth person: 362 / 365, for the fifth person: 361 / 365 and so forth...

To calculate the probability that two people on the same date of birth do not participate in a group of n people, we multiply all of these probabilities together. This gives the probability that each new person will have a different birthday than everyone else who has preceded them. So, for n people, the probability of no common dates of birth is: (364/365). ( 363 / 365). ( 362 / 365)..... (365-N+1/365).

For example, when n = 23, the probability that two people will not share the date of birth is

(364 / 365). ( 363 / 365). ( 362 / 365)..... (343 / 365)

We can calculate this finding using a simple calculator, and the result is approximately 0.4927 (about 49.27%). Now, to find the probability that at least two people share a date of birth, we subtract this value from 1 and find 1−0.4927=0.5073, so the probability is about 50.73% for 23 people.

What when a group is more than 23?

Of course, the probability will increase rapidly: with 30 people (e.g. a classroom), the probability jumps to about 70%. With 50 people (e.g. a train car passenger), the probability is about 97%. With 70 people (people invited to your party, for example), the figure is over 99.9%, which means that two people are almost certain to share the same Christmas Day in a group of 70 people.

The Christmas paradox is a famous example in probability theory, showing how relatively small groups can produce surprisingly high probabilities for certain outcomes (such as shared birthdays). It's a great example of how human intuition often struggles with possibilities, and how our intuition can mislead us, especially when it comes to multiple comparisons. It also clearly shows the flawed logic that we can sometimes use.

![]()

The Other Side of the Business World - 3 Movies You Must Watch

These dramas dive into the dark side of business, exposing greed, betrayal, and ethical compromise. From Zuckerberg's ambition in *The Social Network* to *Boiler Room*’s stock fraud and *The Founder*’s ruthless empire building, they reveal how success can come with a moral cost. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Things people with emotional intelligence never do

Emotional intelligence helps people understand and manage emotions, leading to better relationships, improved teamwork, and stronger mental health. It can be developed through self-reflection, mindfulness, and active listening. Emotionally intelligent people avoid impulsive actions and build balanced lives with better decision-making and communication. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

How to behave in a world of professional chaos: a guide to thriving amid uncertainty

Professional chaos can be your stepping stone to growth—embrace change, stay curious, build resilience, and nurture a flexible mindset. Surround yourself with a strong network, seek advice, and don’t forget to take care of yourself. Chaos isn’t the end—it’s the start of something new. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Simple ways to ascertain the nature of the curved ground

You don't need fancy tools or deep science to see Earth's curve—just use your camera, observe buildings, watch ships at sea, enjoy a flight, explore space photos, witness an eclipse, or study ocean tides. These simple experiences reveal the beautiful, curved nature of our planet in creative and exciting ways. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

The Dream of Getting Rich Quick: Stories of Turning Good Fortunes into Millionaires Overnight

Overnight Millionaires: People Who Got Rich Quick more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Do you know why hair becomes white with age and not skin?

White hair can show up early due to genetics, stress, vitamin B12 deficiency, or smoking. While aging is a natural cause, lifestyle and health factors also play a role. Sometimes, treating underlying issues like thyroid problems or vitamin deficiencies may help restore hair color. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Blood test uses 'protein clock' to predict risk of Alzheimer's disease and other diseases

Blood test uses 'protein clock' to predict risk of Alzheimer's disease in others more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

The Seven Years' War: A Global Conflict Defining a New Era

The Seven Years' War, fought from 1756 to 1763, was the first true global war, reshaping power across Europe, North America, and beyond. It marked Britain's rise as a colonial giant and set the stage for revolutions to come, with Frederick the Great and key battles leaving lasting impacts. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

Tranquility and Beauty in Djerba Island in Tunisia

Djerba, or the "Island of Dreams," enchants with its pristine beaches and rich history. Combining the charm of the Mediterranean, its multicultural heritage, and the spirit of local life, it is an ideal destination for relaxation and adventure amidst breathtaking natural landscapes and authentic cultural experiences. more- ADVERTISEMENT

![]()

The ten most lonely things in the world

The loneliest whale in the world sings at a frequency no other whale can hear. The only tree in a 400 km stretch of desert was hit by a drunk driver. A little robot named Curiosity sings “Happy Birthday” to itself every year on Mars. more- ADVERTISEMENT